Poetry

As an English major, I was exposed to poetry along the way. John Milton’s Paradise Lost comes to mind, as does Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T.S. Eliot, and Dover Beach by Matthew Arnold. I liked them well enough, especially after we analyzed them in class, and I had a better understanding of what the poet was trying to say than I was able to decipher alone in my dorm room. But it wasn’t until I read To Be of Use by Marge Piercy, and Worked Late on a Tuesday Night by Deborah Garrison, and just about anything penciled by Billy Collins, including The Lanyard, which I reread every summer, that I began to enjoy it.

Not all poetry, mind you. If I don’t understand it, I’m not much interested. Recently, I bought at a used bookstore a slim volume (which most books of poetry are) called 100 Selected Poems by E.E. Cummings (or is it e.e. cummings?). Who was responsible for the selecting, I wonder? Clearly not someone who thinks about poetry like I do. I’m all for being educated, but I also like to be amused, gently sharpened, and able to nod in comprehension as my eyes travel the lines and verses. E.E. Cummings, I concluded after the partial digestion of 35 poems, is not my guy.

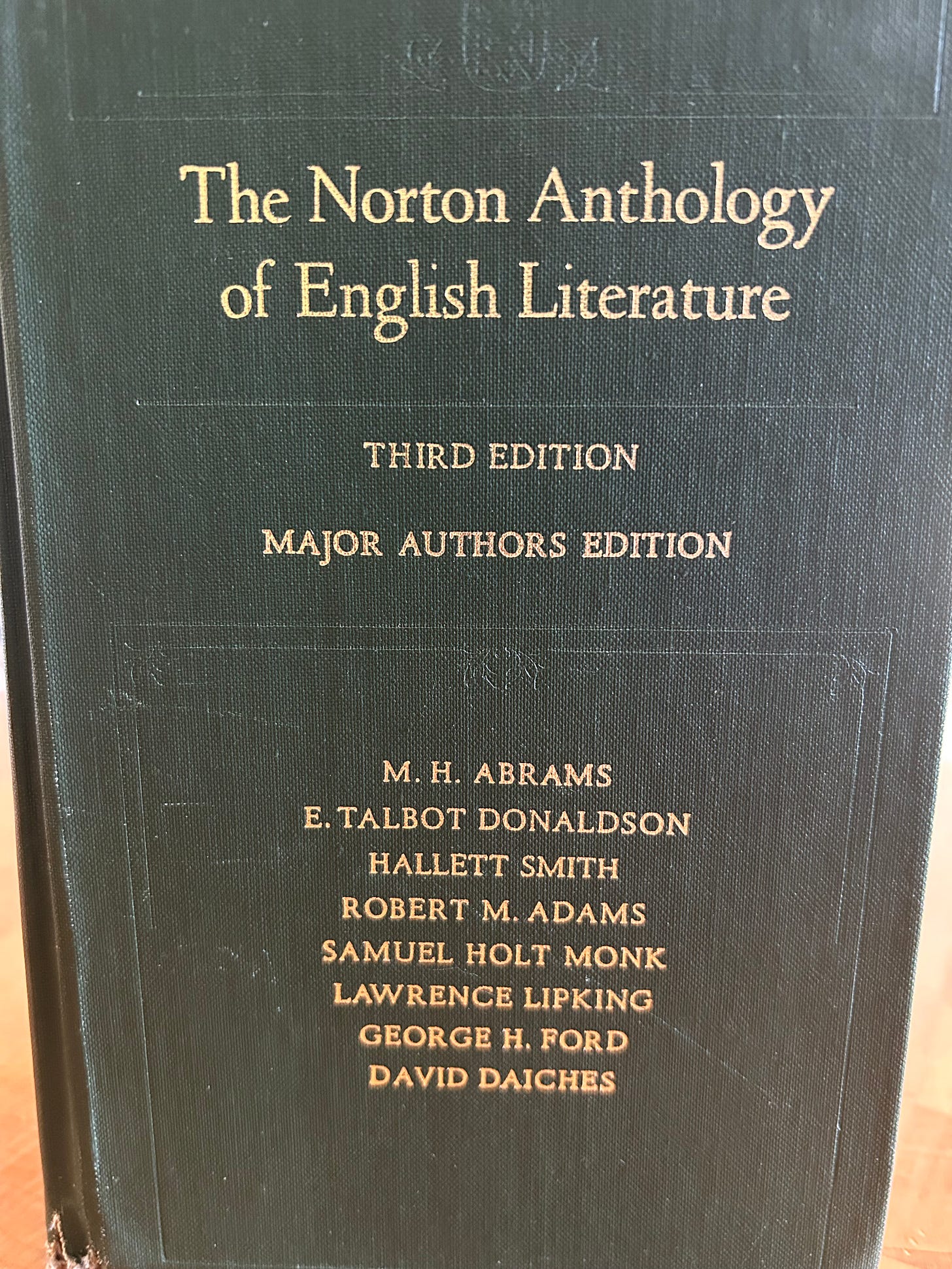

This is my Norton Anthology from college. I loved its tissue-thin pages, its weight, and its broad and voluminous content.

For the last several years, I’ve started my day by reading a poem. I sit at my kitchen island, coffee in hand and reading glasses in place. At the moment, I’m nearing the end of a collection by Margaret Gibson. She lives in Connecticut and has been awarded numerous prizes. In Not Hearing the Wood Thrush, Gibson writes about her late husband’s illness and demise. It’s powerful and sad, and I’m ready for a change. She also writes about nature, as did Mary Oliver, whose poetry speaks to me more clearly and closely than Gibson’s.

A particularly good poem can set me up for the morning. (It can also give me my Wordle word for the day!) Because Ted reads poetry, too, sometimes I share my favorite poems with him, which leads us to discuss and ponder, kind of like I did in college, minus the brilliant professor leading the charge. Without the professor, however, we are able to feel comfortable with our own conclusions. No one knows exactly what the poet meant when writing the words (except the poet), so we’re free to guess!

Reading poetry also, inadvertently, improves my writing. Because most poems are short – usually able to fit on a single page – the language must be precise. Poets – more than essayists, short story writers, and certainly novelists – choose their words carefully and deliberately. They don’t have the luxury of 20 pages, of 300 pages, to tell their story. Brevity is the name of their game. This is something I think about as a writer: not brevity necessarily but word choice. What words are best for what I’m hoping to convey?

Do you read poetry? If so, which poets ring your bell?

Recommendation: If you don’t read poetry but want to give it a whirl, begin with a collection of poems by different poets. One of my favorites is Good Poems, selected and introduced by Garrison Keillor of Prairie Home Companion (and other) fame. In it, you’ll find the two poems by Piercy and Garrison, and a couple by Billy Collins. You can watch him read The Lanyard here.

Hello back to Andrea! It's hard not to like Billy Collins. His genius is clear in his work, but not in a head scratching kind of way. I like his honesty, a trait which has become more and more important to me. Listen to him read The Lanyard. As the mother of three boys, I find it dead on. It's hilarious but also incredibly sweet. The last line gets to me every time.

An interesting perspective on poetry. Personally, I think that whether poets are “better” at word choice depends on the context and purpose. Their selection of words are typically aimed at creating a specific mood or insight. Essayists and novelists tend to use a broader vocabulary to develop ideas and narrative over longer passages. Clarity and storytelling requires a different approach to word choice. I suppose long poems like “The Raven” by Poe and “leaves of Grass’ by Whitman and/ or “Song of Hiawatha” by Longfellow are somewhere in the middle. Thank you for bringing up this interesting subject!!